HONOLULU (HawaiiNewsNow) – About a half dozen federal employees at the historic U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement building downtown blame mold there for asthma and other life-threatening health problems they have suffered for nearly three years. While federal ICE officials denied there are serious environmental problems with the building, some employees said they have faced retribution for filing illness claims.

The building is located at 595 Ala Moana Boulevard, a historic structure constructed in the early 1930s. It’s where federal officers work on customs and immigration investigations as well as enforcement.

“I had difficulty breathing and I was shaking and all these symptoms that I never experienced before,” said Michael Rehfeldt, an intelligence research specialist who said he started feeling bad health effects shortly after he moved into the building in 2011.

The first month Rehfeldt began working with decades-old Chinese immigration documents in his office, he started feeling nauseated and a tingling sensation. His condition landed him in the Queens Medical Center emergency room three times over six months starting in April 2011.

His face turned beet red. After emergency room visits, Rehfeldt was admitted to the hospital each time. He also spent several days in Queen’s intensive care unit during one episode, because he said doctors were concerned he might die.

“That was the scariest part of all, when the doctor in the emergency room told me that he didn’t think I was going to make it,” Rehfeldt said.

An environmental investigation completed in June of 2012 — more than a year after Rehfeldt first became so ill — concluded his sickness could have been caused by iodine in the files he worked on, because he’s allergic to iodine.

But the probe also found glass fibers on his desk, apparently from ceiling tiles.

Eventually, other employees in the office started feeling sick, suffering from difficulty breathing and asthmatic symptoms. That’s when someone called the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to file a complaint.

OSHA teams inspected the building in April of last year and they found air conditioning units that had not been cleaned for years, full of thick, black, sludge-like mold.

“And I was like, appalled actually, by this mold. I mean, it was just dripping down. It was black. It was awful. So I said, ‘Now I understand why I can’t breathe,'” Rehfeldt said.

OSHA slapped the agency with two serious violations, saying managers failed to maintain and clean the air conditioning systems so employees were exposed to toxins from 12 types of mold and as a result developed respiratory illnesses like asthma.

An Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokeswoman said once OSHA found all that mold, ICE immediately called in an air conditioning firm to give the A/C a “thorough cleaning.”

“Subsequent air sampling by Federal Occupational Health personnel determined air quality in the facility to be acceptable,” said ICE spokeswoman Virginia Kice.

The latest testing and survey of the building conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service last November found “Results did not suggest a widespread indoor air pollution problem resulting from the presence of mold, lead, asbestos or arsenic in the office environment,” according to a report obtained by Hawaii News Now.

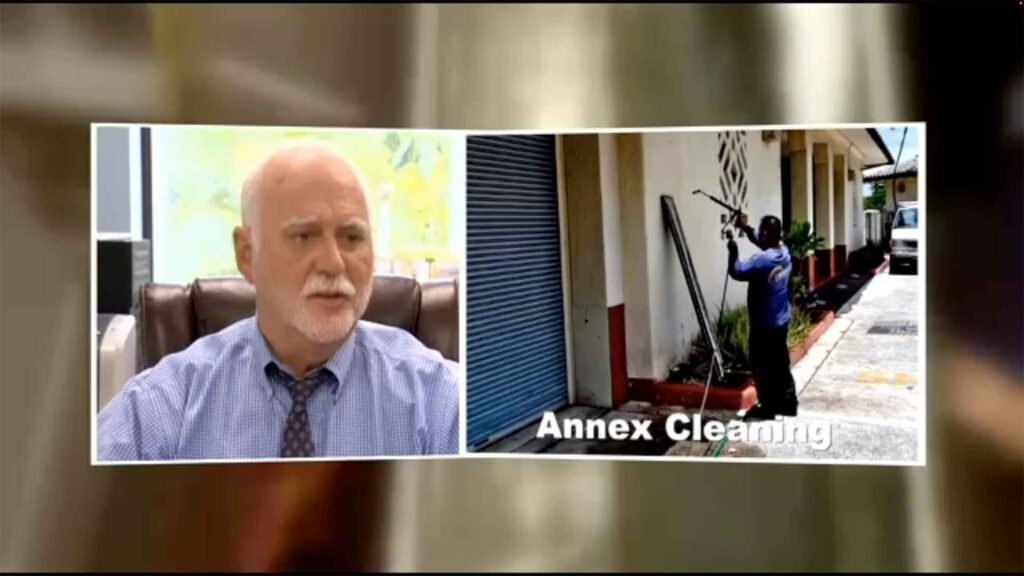

Dr. Scott Miscovich is treating Rehfeldt and about six other federal employees who work in the immigration building for similar symptoms.

“You don’t have to be an epidemiologist to start to look at this clustering effect that’s occurring to really say this is from the exposure,” Miscovich said.

But Miscovich said it gets worse, because some of the molds found in the building are known carcinogens, which can cause cancer. Here’s what he told Hawaii News Now about two of his other patients who work in the building.

“Two of them have manifested very serious cancers. One of them is a very rare immune, allergic-mediated cancer,” Miscovich said.

Because of the moldy conditions, managers temporarily relocated a few employees to other facilities, such as the federal detention center near the airport. But the great majority of them — dozens of others — remain working in the building.

“They’ve been trying to cover this stuff up, I think,” said Elbridge Smith, an attorney representing three employees who have filed workers compensation and equal employment opportunity cases against ICE.

Smith said the agency’s managers repeatedly hired their own cleaners just before inspections to try to lessen documentation of the problem.

“Another cleaning crew came in over the weekend and cleaned the very areas that were going to be inspected the following week to try to make them as clean as possible. And yet, they still uncovered mold and other toxins,” Smith said.

Smith said an administrative supervisor who admonished a subordinate for discouraging staffers from filing workers compensation claims about the mold problems was improperly suspended for creating a “hostile work environment.”

Hawaii News Now has spoken to three other employees who are suffering from ill effects they blame on the building, but they said they are too afraid of retaliation to be identified. A fourth person who works in the building is coughing up blood and suffering asthma problems but doesn’t want to come forward for fear of being ostracized by management, a union representative said.

“Anybody who makes a complaint and anybody who raises this issue is seemingly being blacklisted,” Smith said. “They’re just burying their heads in the sand and hoping this all goes away. But employees are still getting sick.”

Smith accused the agency and its longtime special agent in charge of the Honolulu office, Wayne Wills, of denying, downplaying and minimizing the problems.

A December 2011 air quality assessment conducted in the building was not completed until June 2012, about six months later, even though employees were reporting health problems.

That report called for testing for mold in the air conditioning vents and implementation of a cleaning and maintenance schedule for A/C in the building. But Smith said the agency failed to take proper action until OSHA came in nearly a year later and discovered the extensive mold problem.

Virginia Kice, the ICE spokeswoman, declined to say whether the agency followed those 2012 recommendations.

“Throughout this process, ICE has continued to keep employees informed through town hall meetings and other forms of communication; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is committed to ensuring the welfare and safety of its employees and all those who access this facility,” Kice said in a written statement.

In a separate incident on January 16, a fire hose pipe burst on the building’s first floor, flooding hallways and offices.

All of the flooring in the affected areas of the January incident is being replaced, “out of an abundance of caution,” Kice said. “Once the flooring installation is done, ICE will again have Federal Occupational Health Personnel perform extensive air sampling to ensure the air quality in the facility is acceptable.

“They’re just burying their heads in the sand and hoping this all goes away. But employees are still getting sick,” Smith said.

A December 2011 air quality assessment was not completed until about seven months after on-site tests were performed, in June 2012. Employees said that’s another example of the agency’s slow response to an environmental problem that was making them sick.

“My doctors needed to know what were in those test results. They wouldn’t give them to me so I had to file a FOIA request to get them like seven months later,” Rehfeldt said.

Employees have been complaining about mold and musty smells in the building going back to 2007, when a federal indoor air quality survey found no hazardous organisms were found but “odors were detected in several of the offices.”

The 2007 survey found “stagnation” of air in the building, where carbon dioxide levels doubled over a three-and-a-half hour period, indicating there was a lack of outside air. More than six years ago, the survey recommended circulating more air in the offices by keeping air conditioning fans in the “on position” all the time, even if the air wasn’t being cooled. And the survey said a cleaning schedule needed to be followed. Employees said those recommendations were never followed, leading to worsening environmental problems in the building.

The ICE spokeswoman declined to answer questions about the agency’s response to the 2007 report and recommendations.